|

Though Batman's rogue's gallery

is arguably the greatest in comics, the early Bronze Age

saw the Joker, the Riddler and Catwoman sidelined in favor

of more conventional killers, gangsters and lowlifes, and

the occasional supernatural terror.

The

hugely popular live-action television show of the 60s had

conferred an unprecedented celebrity to Batman's more colorful

foes, but it had also made them symbols of high camp to

the general public. As the 70s dawned, DC Comics was determined

to return Batman to his roots as a "dark avenger of

the night," and as shadows and dark alleys re-entered

the visual lexicon of the books, the brighly colored supervillains

of an earlier age were sent packing. In their place came

a new collection of villains more in keeping with the more

"realistic" and spooky spin given to the Bronze

Age Batman. The

hugely popular live-action television show of the 60s had

conferred an unprecedented celebrity to Batman's more colorful

foes, but it had also made them symbols of high camp to

the general public. As the 70s dawned, DC Comics was determined

to return Batman to his roots as a "dark avenger of

the night," and as shadows and dark alleys re-entered

the visual lexicon of the books, the brighly colored supervillains

of an earlier age were sent packing. In their place came

a new collection of villains more in keeping with the more

"realistic" and spooky spin given to the Bronze

Age Batman.

Easily the most important of these was Ra's Al-Ghul,

an evil genius whose mad dreams of reshaping the world led

Batman on a series of James Bond-style international exploits.

Throughout the 70s and into the 80s, Batman would pursue

Ra's across arid deserts, through snow-capped mountains

and finally even to outer

space. Like the Bond villains he resembled, Ra's had

a global network of loyal agents and high tech, secret bases.

Plus of course a beautiful female helper who falls in love

with the hero, only this time she was Ra's own daughter,

Talia, and Ra's actually approved of the romance. In fact,

when he wasn't trying to take over the world, Ra's chief

hobby was trying to make Bruce Wayne his son-in-law. Several

adventures seemed to end with the villain's demise, only

to see him later resurrected in his "Lazarus Pit,"

a literal deux ex machina which, it was suggested, had been

keeping him alive for centuries.

Harking

back to Batman's earliest days in Detective Comics,

there was a new emphasis on supernatural foes, from vampires

to werewolves to immortal madmen. Most of these were one-off's

but one "monster" foe who came to stay was Man-Bat,

a grotesque figure combining a bat's ears, wings and talons

with the body of a man. In reality bat-researcher Kirk Langstrom,

Man-Bat set out to fight crime alongside the Caped Crusader,

but often ended up battling him instead. Treated alternately

as a villain, a hero and a nuisance, Man-Bat attracted enough

of a following to co-star in several issues of Brave

and the Bold before getting his own title (for a mere

3 issues). Harking

back to Batman's earliest days in Detective Comics,

there was a new emphasis on supernatural foes, from vampires

to werewolves to immortal madmen. Most of these were one-off's

but one "monster" foe who came to stay was Man-Bat,

a grotesque figure combining a bat's ears, wings and talons

with the body of a man. In reality bat-researcher Kirk Langstrom,

Man-Bat set out to fight crime alongside the Caped Crusader,

but often ended up battling him instead. Treated alternately

as a villain, a hero and a nuisance, Man-Bat attracted enough

of a following to co-star in several issues of Brave

and the Bold before getting his own title (for a mere

3 issues).

Other Bronze Age foes included The Spook, a cloaked

killer who could escape Gotham Penitentiary seemingly at

will, the improbably outfitted Calculator, and a

third version of Clayface, this one with the

ability to reduce victims to puddles of protoplasm with

a mere touch of his diseased hand.

Meanwhile,

the allure of Batman's A-list villains soon proved irresistible

and they made their inevitable return, albeit in ramped-up,

newly lethal forms. The Penguin and the Riddler

became more dangerous and less comical. Two-Face,

whose acid-scarred face kept him sidelined throughout the

kid-friendly 50s and fun-loving 60s, now took his place

among the top ranks of Bat-villains in the horror-tinged

70s. Hugo Strange, AWOL since Batman #1, returned

with his Golden Age, monster-making M.O. intact. Meanwhile,

the allure of Batman's A-list villains soon proved irresistible

and they made their inevitable return, albeit in ramped-up,

newly lethal forms. The Penguin and the Riddler

became more dangerous and less comical. Two-Face,

whose acid-scarred face kept him sidelined throughout the

kid-friendly 50s and fun-loving 60s, now took his place

among the top ranks of Bat-villains in the horror-tinged

70s. Hugo Strange, AWOL since Batman #1, returned

with his Golden Age, monster-making M.O. intact.

No villain went through more changes in this period than

the Joker. Portrayed in the 50s and 60s as a larcenous

prankster devoted to humiliating Batman with corny gags,

the Joker returned to Batman's world in the 70s as a homicidal

maniac, a four-color nightmare who proved that yes, kids,

clowns can indeed be scary. In the classic and oft-reprinted

"Joker's Five-Way Revenge," (Batman

# 251) writer Denny O'Neill and artist Neal Adams presented

a Joker unseen since the earliest tales of the Golden Age;

a psychotic killer who left his victims' faces twisted into

horrible smiles. Later Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers

would complete the Joker's evolution into a true madman

who "masterminded" such insane plots as putting

smiles on schools of fish in order to copyright seafood

and earn millions in royalties.

Before slipping into abject madness, the Clown Prince of

Crime made history of a sort by being spun off into his

own magazine, easily one of the oddest experiments in DC's

history to that point. In the nine issues of his own book,

the Joker escaped repeatedly from his cell at Arkham Asylum

to travel the country in his "Ho-ho-home on wheels"

and match wits with fellow villains Two-Face, the Scarecrow,

Lex Luthor and (perhaps inevitably) The Royal

Flush Gang. Also joining the fun were heroes Green

Arrow and the Creeper. This version of the Joker,

primarily written by Denny O'Neill was somewhere between

the "old" and "new" models; a prankster

more comic than lethal; dangerous to be sure, but not the

homicidal killing machine he would later become. And small

wonder...devoting a book to a villain was challenge enough,

but making a murderous lunatic into a protagonist was too

tall an order even for a comic book writer.

A memorable four-part story line saw Batman's rogues gallery

take center stage. With the hero apparently deceased, the

Joker, the Riddler, Lex Luthor (!) and others claim to have

done him in, and one by one enter "testimony"

before a jury of their fellow villains to determine who

will get the credit. In another memorable arc, Batman himself

becomes Public Enemy Number One when it appears he's fatally

shot Talia in the back...with Commissioner Gordon himself

as witness. For the next few months, Batman has to stay

one step ahead of Gordon and his men as he struggles to

clear his name.

In all, the Bronze Age was a great time for Bat-villains,

with new ones joining the rogue's gallery and older ones

taking on a greater sense of menace. But of course no era

can be truly "great" from the bad guys' point

of view. In the end, they're always going down!

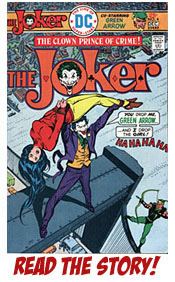

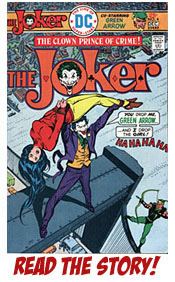

A GOLD STAR FOR THE JOKER

In

issue #4 of his own book, the Clown Prince of Crime matched

wits not with the Caped Crusader, but with the Emerald Archer.

Oliver (Green Arrow) Queen and Dinah (Black Canary) Lance

guest star in this off-beat tale that reflects the odd stage

of transition in which the Joker found himself in the 70s. In

issue #4 of his own book, the Clown Prince of Crime matched

wits not with the Caped Crusader, but with the Emerald Archer.

Oliver (Green Arrow) Queen and Dinah (Black Canary) Lance

guest star in this off-beat tale that reflects the odd stage

of transition in which the Joker found himself in the 70s.

The Joker's scheme here falls somewhere between the flashy

pranks of his TV days and the genocidal excesses of modern

comics. Similarly, there is an odd dynamic at work in a

tale featuring a protagonist who (a) is a self-confessed

raving nut job and (b) leaves a body count in his wake.

Perhaps in deference to the comics code, the Joker seems

to meet his demise at story's end, but given that the next

panel advertises his adventure for the following month,

it's hard to count him out.

Two Superman alums handle creative chores on this one,

with Elliot

S! Maggin writing and Jose

Luis Garcia Lopez on pencils. Maggin had an affinity

for Green Arrow that shows through here, and Lopez's layouts

and figures are so masterfully rendered that, for once,

even an ink job by the dreaded Vince Colletta can't spoil

the fun.

No Batman in this one (except for a brief "cameo"...don't

blink!), but "Gold

Star for the Joker" provides a great example of

one of the odder offshoots of Bat-mythology in the Bronze

Age.

|